Sonia Delaunay

collection PINTON

The first mention of tapestry in the Marche county dates back to 1456 in Felletin. Since then Aubusson tapestry has experienced an initial wave of extraordinary success followed by challenging times before regaining its glory and identity, to the extent that the term aubusson has become a common noun since the XIXth century.

AUBUSSON TAPESTRY:

MYTHS, HISTORY AND HERITAGE

Mysterious Origins

The origins of Aubusson tapestry remain a mystery, and legends abound. For some, Aubusson tapestry dates back to the Moors who settled in the area after being defeated in Poitiers in 732 AD. In the XIXth century, George Sand mentions that tapestries made in Aubusson were decorating the walls of the Bourganeuf Tower, 40km away from Aubusson, where Prince Zizim was imprisoned in the XVth century. This was enough to give rise to a new legend, according to which the exiled Prince took with him some Turkish weavers who established their technique in the area. Finally, many defend the idea that tapestry was introduced by Louis I de Bourbon, Comte de la Marche, and his wife, Marie de Heinaut, who brought Flemish weavers to Aubusson and Felletin. All concur however to say that the acidic water characteristic of the Creuse district removes the grease from the wool and feeds the dyeing workshops.

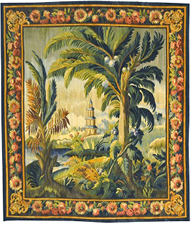

XV-XVIIth Centuries: Greenery and Mythology

Towards the end of the XVth century and during the XVIth century, Aubusson tapestry enjoyed great popularity. It was the heyday of verdures (greenery) – the floral patterns or “millefleurs” favoured in the XVth century gave way to cabbage leaves or “feuilles de choux” in the XVIth century. The central panels drew inspiration from hunting, religion or mythology, with luxuriant and mysterious flora populated with real of fantasy animals. Fashion changed in the XVIIth century, and some panels began to take inspiration from sentimental novels.

Very quickly European nobility developed a passion for tapestry. Large narrative panels bringing together multiple scenes from the same story were hung on castle walls to create vibrant backgrounds and protect against draughts.

ancient tapestry

PINTON collection

139×154 cm

courtship scene

Aubusson Mill, 18th century

260×230 cm — collection PINTON

Aubusson Tapestry in the XXIst Century

At the end of the XXth century, tapestry was running out of steam. Many craftspeople were retiring. And, despite the creation of ENAD, no corpus of weaving techniques had been written. The transfer of know-how was in danger.

In addition, tapestry had gone out of fashion and seemed to belong to a bygone past, to the outdated decor of the bourgeois sitting-rooms of yesteryear. However, driven by its inclusion in the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of the UNESCO, Aubusson started to experiment again. Maison PINTON, in particular, was instrumental in reviving the special relationships with artists: invited to collaborate with craftspeople, plastic artists, designers, painters and street artists are now taking over the international contemporary art market with their original creations. Each model is limited to 8 copies with the issue number, the artist’s signature and the logo of the workshop woven into the tapestry. As heir to this long-standing tradition and determined to continue training new weavers and to take innovation even further, PINTON is still writing the history of the Aubusson tapestry.

1665: the Aubusson Royal Manufactory

In the XVIIth century, Louis XIV signed the Orders and byelaws governing the merchants, masters and tapestry makers of the city of Aubusson, which laid a number of rules including the requirement to control the quality of the raw materials used and the finished products, or to weave the label MRDA, standing for “Manufacture Royale d’Aubusson” (Aubusson royal manufactory), in the selvedge area of each tapestry. Colbert granted every workshop in Aubusson the title of “Manufacture Royale de Tapisseries” (royal tapestry manufactory) without bringing the weavers together within a large manufactory. The weaving industry was severely impacted by the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 because many weavers were Protestants and more than 200 of them left the city.

XVIII-XXth Centuries: Decline and Renaissance of Aubusson Tapestries

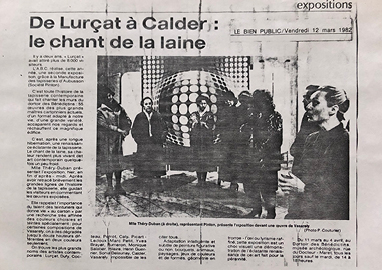

After these troubled times, the manufactory underwent deep reforms in the XVIIIth century and experienced renewed popularity. To cater for changing tastes, tapestries now showcased secular themes, country scenes and childhood games, as well as the “chinoiseries” (Chinese patterns) that were very fashionable at the time. The industrial revolution of the XIXth century led to the creation of large manufactories controlling the production chain, from painting the cartoons, to spinning and dyeing the wool, to weaving. This period was also marked by the development of upholstery: chairs, armchairs, screens or trunks became covered in tapestry. At the same time, Aubusson floor coverings took a back seat in favour of low-pile or knotted rugs. The creation of ENAD, École Nationale d’Art Décoration d’Aubusson (the national school of decorative arts of Aubusson), and its successive directors, in particular Antoine-Marius Martin and Jean Lurçat, gave tapestry a new lease of life. They reduced the number of colours, used thicker yarns, introduced colour-coded cartoons, all of which contributed to revolutionise tapestry and attract major artists such as Calder, Vasarely, the Delaunay or Picasso who combined their creations with the know-how of the cartoon designers and weavers.

article from le bien public, 1982

image © archives PINTON